Astronomers have revealed the largest known structure in the universe, which is made up of not only clusters of galaxies but also clusters of these clusters that form a gravitationally interacting unit.

In fact, the superstructure is estimated to hold an almost inconceivable 200 quadrillion (that's 200 followed by 15 zeros) times the mass of the sun and is more than 1.3 billion light-years long, larger than the Milky Way.

Quipu, as it is called, was discovered by an international team led by Germany's Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE). Their study describing the superstructure has been accepted for publication in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. A preprint is available on the arXiv server.

Quipu was named after the knotted cords used as recording devices by the Inca Empire and other South American cultures. It resembles those cords, with one long main filament off which branches many side strands.

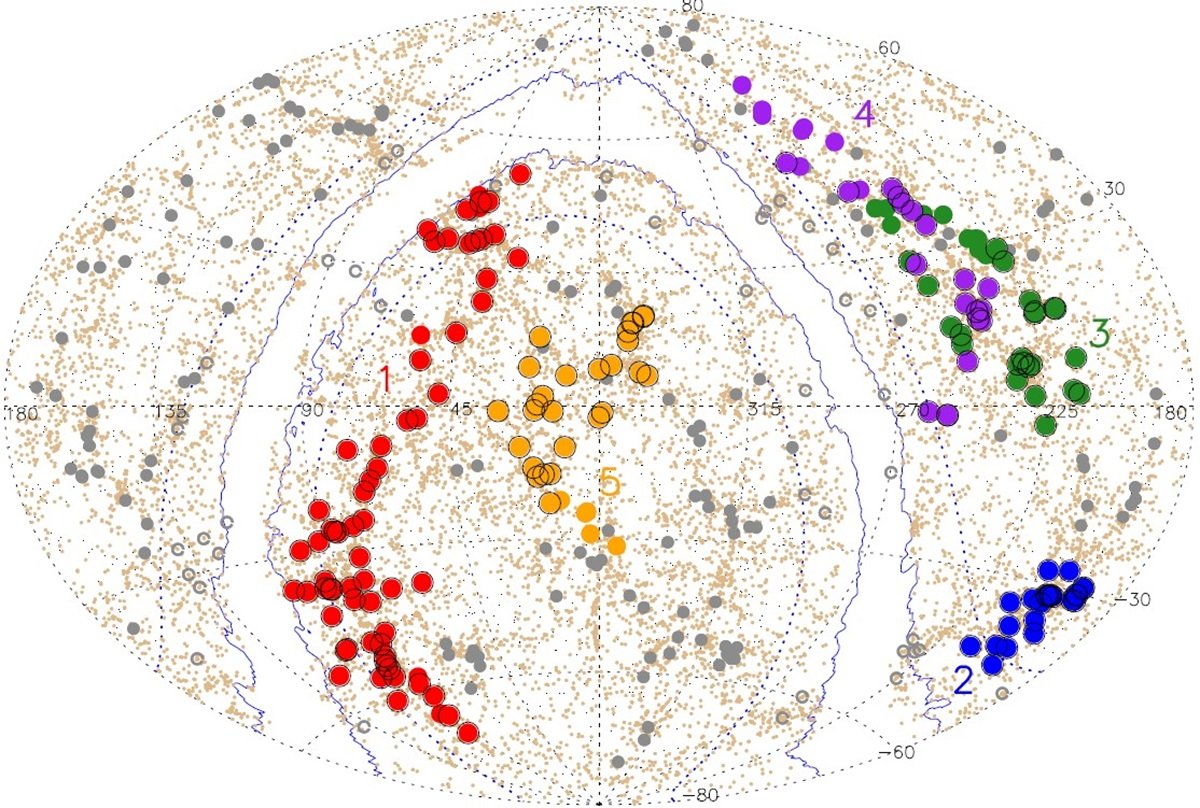

In their study, MPE astrophysicist professor Hans Böhringer and his colleagues report the detection of five superstructures within the known universe—at a distance of between 424 million and 815 million light-years from the Earth—with Quipu the largest.

Quipu is joined by the Serpens–Corona Borealis (at 0.76 billion light-years long), Sculptor–Pegasus (0.70 billion) and Hercules (0.50 billion) superstructures.

Quipu, Hercules, Serpens–Corona Borealis and Sculptor–Pegasus are all larger than the fifth and final superstructure highlighted in the study, the Shapley supercluster, which had previously held the record for the largest supercluster. It has now been bumped down to second most massive.

Together, the researchers said, the five superstructures contain around 45 percent of the galaxy clusters, 30 percent of the galaxies and 25 percent of the matter in the known universe.

At the moment, the mass of these superstructures is keeping them together, but this will not last forever, Böhringer said. Eventually, they will be broken up into smaller units, although this will take a while—several times the present age of the universe, in fact.

Understanding the universe's large-scale structure is important for astrophysicists for a number of reasons, Böhringer told Newsweek.

"When we do observational measurements to understand which cosmological model describes our universe, we generally make the well-justified assumption that the universe is approximately homogeneous [uniform throughout]," he explained.

"However, we have to take into account that we are surrounded by superstructures and voids which modify these observations on the few percent scale," he said.

One example of how this plays involves the calculation of the Hubble constant—the expansion rate of the universe.

"If there are massive structures in one direction while we have a void in the other direction, we should note a slight difference in the measurement of the Hubble constant with local distance estimators," Böhringer said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about astronomy? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Reference

Boehringer, H., Chon, G., Truemper, J., Kraan-Korteweg, R. C., & Schartel, N. (2025). Unveiling the largest structures in the nearby Universe: Discovery of the Quipu superstructure (No. arXiv:2501.19236). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.19236

Is This Article Trustworthy?

Is This Article Trustworthy?

Newsweek is committed to journalism that is factual and fair

We value your input and encourage you to rate this article.

Newsweek is committed to journalism that is factual and fair

We value your input and encourage you to rate this article.

About the writer

Ian Randall is Newsweek's Deputy Science Editor, based in Royston, U.K. His focus is reporting on science and health. He ... Read more